By Lorna Bointon, Sea Watch Foundation Regional Coordinator

Found in every ocean, orcas, or killer whales, are apex predators at the top of the food chain and, along with other cetacean species, provide a visible indication of ocean health.

A pod of orca / killer whales off the Caithness coast. Photo credit: Colin Bird/SWF

The sea may reflect the UK’s changeable weather, ranging from stormy grey to dazzling azure blue, but from a cetacean’s point of view, it’s all black and white, or at least grey. Studies indicate that orcas, along with other cetacean species, do not have the necessary optical cells / cones to see colour in the blue spectrum and rely instead upon rods that are used for discriminating contrast.

Of course, orcas are easily recognised by their black and white body colours. The monochrome patterning helps to act as camouflage, breaking up appearance, much as warships used ‘dazzle’ camouflage paint on their vessels to affect perception of appearance, speed and direction. They also boast the tallest dorsal fin of all cetacean species with the fins of adult males reaching up to 1.8 metres. The grey saddle patch behind the dorsal fin tends to vary between animals acting as a means to recognise different individuals. The name ‘orca’ translates as ‘barrel shaped’, a reference to their body shape.

Hunter Killers

The towering dark dorsal fin may be the first thing that an unfortunate prey animal may see of this formidable predator as it slices through the water. Efficient hunting techniques and collaborative behaviour make them redoubtable and intimidating predators. They are intelligent and capable of communicating particular hunting strategies within groups, known as pods, in a bid to herd prey. They also may collaborate and share food with other group members. As with other dolphin species, there is a strong social bond which may last through their lifetime.

Despite a body weight of up to 6 tonnes, orcas are built for speed with males reaching record breaking speeds of 55.5 km/h, making them the fastest of any marine mammal.

As well as differences in body size and weight, sexual dimorphism is apparent in the dorsal fin shape and size with male dorsal fins being taller and more triangular, whilst the dorsal fins of females are shorter and recurved.

Male orca from the West Coast Community, in the Hebrides . Photo Credit: Peter Evans/SWF

An adult female orca with calf in North Scotland. Photo Credit: Colin Bird/SWF

As with other cetacean species, orcas live in complex hierarchical structures with strong bonds existing between pod members. Mature females are usually dominant within the pod with males often forming separate associations with other males, although they will also regularly link up with females.

Orca calves may remain within family pods throughout their lifetime. Photo Cedit: Ryan Nisbet

Ecotypes

With orcas, it’s not all black and white, with some pods exhibiting distinct genetically different characteristics depending on their global distribution, with differences in diet, vocalisations, family group size and hunting techniques. Even the white eye patch can differ depending on their ecotype.

Prey items for our Atlantic Type 1 Orcas are mainly fish, such as herring and mackerel, but they may also hunt and kill seals and porpoises for food.

Orca investigating a seal colony in Shetland. Photo Credit: Peter Evans/SWF

Orca killing a harbour porpoise in North-east Scotland, June 2021. Photo Credit: Steve Truluck

In other parts of the world, orcas are also known to attack great white sharks and even to hunt down the largest whale on Earth, the blue whale, chasing it until it is too exhausted and weak to continue.

What’s in a name?

Although commonly referred to as whales, orcas are actually dolphins within the family Delphinidae.

The common name ‘killer whale’ is thought to be derived from ‘whale killer,’ a name coined after sailors witnessed orcas hunting and killing other dolphin and whale species.

Chain reactions

Being an apex predator taking other marine mammals such as harbour porpoise and seals means that pollutants, that have accumulated and cycled through the food chain, end up being ingested by these majestic animals. Sadly, this makes the orca one of the most contaminated animals which can affect their ability to reproduce. One female orca in the Scottish Hebrides, locally named Lulu, became entangled in fishing ropes and sadly died. On analysis, its levels of PCBs (Polychlorinated Biphenyls, a by-product of the plastics industry) was amongst the highest ever recorded.

Orcas face many threats from human sources. Photo Credit: Peter Evans/SWF

Along with pollution, other threats on a global scale include loss of habitat, overfishing leading to prey shortages, entanglement in fishing gear, hunting and live capture for aquaria.

Orca Watch 2021

Started ten years ago in May 2011 by Sea Watch Regional Coordinator Colin Bird and now managed for the charity by Hannah Parkinson, Orca Watch is an annual national recording event held over ten days at John O’Groats, with watches being held around Caithness, North Sunderland, Orkney and Shetland. Volunteers who wish to be involved in this worthwhile and exciting citizen science project are warmly welcomed.

It’s not all about orcas, during the watches you’ll also get the opportunity to spot other marine mammal species. In 2021 Orca Watch was held online but this didn’t dampen the enthusiasm of our volunteers and, along with orcas, we recorded 5 different cetacean species:

- Bottlenose dolphin

- Harbour porpoise

- Minke whale

- Risso’s dolphin

- Common dolphin

In addition to this, we also recorded both UK species of seal – the grey seal and harbour seal - and basking sharks!

Last year’s efforts were the result of 54 hours of observation across 71 land watch sites with 154 sightings reported, comprising 747 individual animals.

Ready for that ‘killer’ shot. Photo Credit: Peter Evans/SWF

How your efforts help conservation

Sightings are important because they give us information about where and when species occur, from which we can identify important areas and habitats, as well as determine changes in their status and distribution. Such knowledge helps provide better informed conservation measures.

Eyes on the prize. Photo Credit: Chiara Giulia Bertulli

The collation of information on abundance and distribution of whales, dolphins and porpoises is valuable in many ways. Besides increasing our general knowledge of the cetacean fauna that inhabits the seas around the British Isles, it can inform us of important areas and times of year for particular species, enabling better decision making on the risk of harm to local populations from certain human activities. It may also indicate where dedicated research should be directed or draw attention to possible status changes both regionally and on a wider basis.

Taking environmental data, such as water depth, sea surface temperature, salinity, and measures of primary productivity, alongside recording species, helps to build up a profile of habitat requirements to help inform better protection measures, such as establishing Special Areas of Conservation.

Observations supplemented by photographs help us to track individuals and determine their ranging movements. One distinctive animal, nicknamed “John Coe” has been followed around the west coast for four decades. Although mainly seen in the Hebrides, in 2021, he was photographed also in SW Cornwall, the Strait of Dover and SE Scotland.

“John Coe” is a distinctive member of the West Coast Community. Photo Credit: Peter Evans/SWF

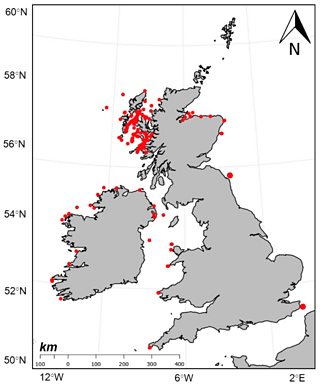

The Wanderings of “John Coe”, 1980-2021. Sources: SWF, HWDT & IWDG

A ‘pod’ of citizen scientists recording effort related data. Photo Credit: Peter Evans/SWF

Orca Watch 2022 – Calling all citizen scientists!

Every year, Orca Watch relies on a pool of volunteers – both locals and visitors – to take part in timed watches collecting data for us using Sea Watch protocols.

We are inviting both experienced watchers and novices to register to become Orca Watch Volunteer Observers, responsible for conducting land watches around Caithness and North Sutherland and/or watches from the John O’Groats ferry. The data collected will be added to Sea Watch’s national database, recognised as the largest and longest running scientific data resource of its kind in Europe, to help monitor the abundance of whales and dolphins in the area. This information is used to help shape conservation measures at government level.

This year Orca Watch is running from May 28th to June 5th. Our base for the event is at John O’Groats, but watches take place all around the Orca Watch area, both from land and from the John O’Groats passenger ferry. Everyone is welcome to take part in the event (subject to any Covid-19 or related restrictions in place) to help us collect data or simply to look out for whales, dolphins and porpoises.

We also hope to hold our popular evening of Orca-related themed talks, as well as smaller events throughout the week.

Orca Watch is very much a citizen science project, and we welcome volunteers who wish to help by collecting effort-related data during the event, as part of our team of Orca Watch Volunteer Observers.

Head to our website to find out how more about Orca Watch 2022, and how you can get involved. https://www.seawatchfoundation.org.uk/orca-watch-2022/