BBC Computer Literacy Project: Taking a look back at the future

David Allen

Former BBC producer

Tagged with:

On Wednesday 9 September, the BBC launched a major content season of programmes and content across TV, Radio and Online to mark the next wave of BBC Make it Digital activity. As part of the season, the BBC Four archive collection Back to BASICS is available on BBC iPlayer, giving viewers a chance to look at programmes from the 1980s when the corporation launched the BBC Micro and the BBC Computer Literacy Project. Producer of the project, David Allen takes us through some of the highlights from those shows.

During the BBC's Make it Digital 'Year of Code', warm references have been made to our 1980s computer literacy campaign, featuring the BBC Micro. I happened to be in the right place at the right time and became a producer and editor of the project from 1979 to 1987 - a time when computing came into the home and the school. Looking back through rose tinted spectacles at our early research and over 120 hours of TV explaining and reporting 'the new technology', I get a curious perspective on today. For good or ill.

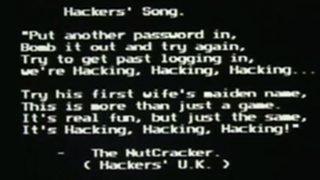

Hackers gained access to the BBC email during a live show

In one live programme in 1982 hackers broke into our demo of electronic mail (then a novelty in the UK, though we'd seen it in offices in the USA in 1979) and showed that passwords can be computed, guessed or leaked (I never quite got to the bottom of how it happened). The next programme featured silhouetted teenage figures talking about how easy it was to hack accounts. Sound familiar?

Lesley Judd with fellow Micro Live presenters

Mobile phones

We explained with some nice graphics created on the BBC Micro how cellphone systems work and Lesley Judd, riding round the doughnut at Television Centre in a Sinclair C5 made (we believe) the first televised mobile to mobile international call - to our reporter in New York who was standing in a snow storm on the top of the Rockefeller Centre. Around that time I was photographed on the tube for the Guardian using one of these novel brick-sized phones. I asked them to make sure I was seen with the train in the open air but they printed one shot in a tunnel where, of course, there was no signal. We still haven't cracked how to make a phone call underground between Bond Street and Oxford Circus.

Voice recognition

I only recently discovered that I can dictate emails and texts using speaking directly into my iPhone. The accuracy is amazing but the system only works if you're connected to 3G or Wifi. The computing power needed to understand any voice without training is awesome and we covered early attempts back then.

Nowadays this is of course all part of cloud computing where your stuff is stored and processed 'up there' in a massive computer somewhere. But maybe what seems a benign and useful feature could turn nasty. Up there 'they' know what you're saying and rumours that mikes and cameras on seemingly dormant phones can in fact be monitored is a bit worrying. Maybe it's an urban myth. Data privacy was an issue back in 1979 - in Nordic countries. Our own data protection act wasn't until 1999. Keeping your data safe now seems a bigger issue than ever.

Presenter Ian McNaught Davis

Making a film

When we started filming for The Silicon Factor in 1980 a BBC film crew could consist of 8 people (sound recordist, sound assistant, cameraman, assistant cameraman, 'sparks' and maybe assistant sparks, director and production assistant). It would often take hours to light a shot. Now I sit at my computer and edit broadcast quality material which I can shoot on my own using 'available light' on a moderately cheap camera and using a computer with up to 4 terrabytes of storage. The BBC Micro had 32K. Film cameras used 400 foot rolls at £100 for 10 minutes (a lot of money in 1980). I can shoot hours of video on a re-usable 64GB flash card for a few pounds. Moores Law (computing power doubles every eighteen months) still seems to hold true.

BBC micro computer

Word Processing

We were among the first in the BBC to write scripts using a word processing package. Nowadays I get irritated by too many features in today's versions of Word or at programs that worked well on an early version of my operating system but are no longer supported. I still keep a typewriter in the attic and remember a programme in which celebrities were invited to try word processing for the first time. One of them was John Humphrys, who just couldn't get anything to work and kept saying how he preferred his old Underwood. I wonder if he still does.

Screens

The received wisdom about UK technology is that we innovate but fail to develop and market. Several examples come to mind around the old British company STC in Harlow where we filmed in 1984. STC pioneered fibre optics, the lack of which is holding up today's fast broadband. STC also in the mid 1980s developed a flat screen device which kept its image after it was switched off and used no power until the image was changed. The company failed to develop and market anything and a year or so later was sold off. It's possible that had it gone on the develop the technology, a Kindle-like British product might have appeared earlier.

Ian McNaught Davis introduces a robot that has pinpoint precision

Robots

Stephen Hawking has been linked to warnings of artificial intelligence leading to 'killer robots'. Our own experience of robots has been more benign. The late and much missed Ian McNaught Davis (Mac), presenter of most of the BBC Computer series was filmed showing how a huge industrial robot could delicately make a hole in an egg, whirl around and put the pin back through the same hole. His payoff was a typical Mac joke, ‘You might ask why anybody would want to use a £35,000 robot to put a pin hole in an egg? Well the answer’s quite straight forward, it’s to stop the egg from cracking when you boil it.'

David Allen was producer and editor of the BBC Computer Literacy Project.

- Find out more about Make it Digital.

- Take a look at the BBC Four archive collection.

- Watch David Allen’s lecture about the BBC Computer Literacy Project on The National Museum of Computing website.