In the middle of the City of London, geologist Ruth Siddall is pointing at a greyish-brown shape, embedded in the stone of a building – and she is delighted.

We're near London's iconic St Paul's Cathedral, with tourists milling around us, many of them staring upwards to the grand dome above. Siddall, however, is leaning forward to peer at a fossil at waist height, embedded within a block of limestone from the Jurassic period. "It's the only one I've seen in looking at acres of stone," she explains. And it comes from a creature that you'd never expect to find on the side of a building.

Siddall is an "urban geologist" who specialises in the stone of the human-built environment – exploring its provenance, fossil content and other interesting features. And today she is taking me on a walking tour of her finds in a busy corner of London, showing me unusual rocks and secret fossils that most people would walk straight past without noticing. I'm learning that if you look a little closer at the architecture, street furniture or pavements of a city, you can often find a hidden world of geology and history – and occasionally even a grey-brown shape on the side of a building that might be a dinosaur bone.

Ruth Siddall pointing at a special fossil find near St Paul's cathedral (Credit: Richard Fisher)

Siddall is one of many urban geology enthusiasts around the world. Some are retired earth scientists; some straddle the gap between archaeology and geology, while others are simply dedicated amateurs. Whether it's Paris or Washington DC, there's usually someone in a city interested in the provenance of the building stones. If you search the hashtag #urbangeology on a social media site, you can usually find various sightings of interesting stones and fossils from around the world: corals at Saks department store in New York; ammonites on the floor of Berlin airport; or molluscs in the black marble of a Tokyo mall, to name a few.

Siddall herself began her fascination with the topic in Greece. In her first job after her PhD, she worked at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, where she was given the task of identifying stones collected from ancient ruins. "I was cataloguing their rock collection, which had been collected by centuries of archaeologists and just piled up in a big heap. They needed a geologist to identify these stones."

Following the Great Fire of London in 1666, London's authorities had extensive rebuilding to do

Equipped with this schooling in building stone identification, she returned to the UK and began to explore the urban environments of her home country. Eventually, this led herand her friend Dave Wallis to build a website where people could locate and submit urban geological finds for themself: London Pavement Geology, which now reaches across the UK. She also leads walking tours, and has published self-guided routes that people can follow in London and elsewhere.

Ruth Siddall's walking tour includes a stop near St Paul's Cathedral in London (Credit: Richard Fisher)

After discovering her website and walks, I asked Siddall for a tour of the City of London on a recent summer's day. We meet for coffee near Paternoster Square, where Siddall introduces me to the most prevalent – and grand – stone of the area.

Compared with the rest of London, the pale buildings in this part of the city, she explains, often share a particular geology. Many of them were built with Portland Stone, a limestone quarried on the Isle of Portland in Dorset, which is one of the UK's most historically significant building stones. Following the Great Fire of London in 1666, London's authorities had extensive rebuilding to do. Admiring the grand marble structures of Italy, but lacking much of that rock on mainland Britain, they embraced their own version. It was a limestone that shared marble's creamy-white appearance. A massive amount of the stuff was quarried to build St Paul's Cathedral, and many other post-fire buildings. Later, it was added to Buckingham Palace too.

Over the centuries, Portland Stone would be shipped across the world. Sometimes, it was for colonial reasons: to place buildings overseas that represented how the British Empire saw itself. But also because of its durability and appearance. For example, it forms part of the United Nations General Assembly Building, built in New York City in the 1950s.

Two different types of Portland Stone – plain blocks and fossil-rich – offer architects the opportunity to make design choices (Credit: Richard Fisher)

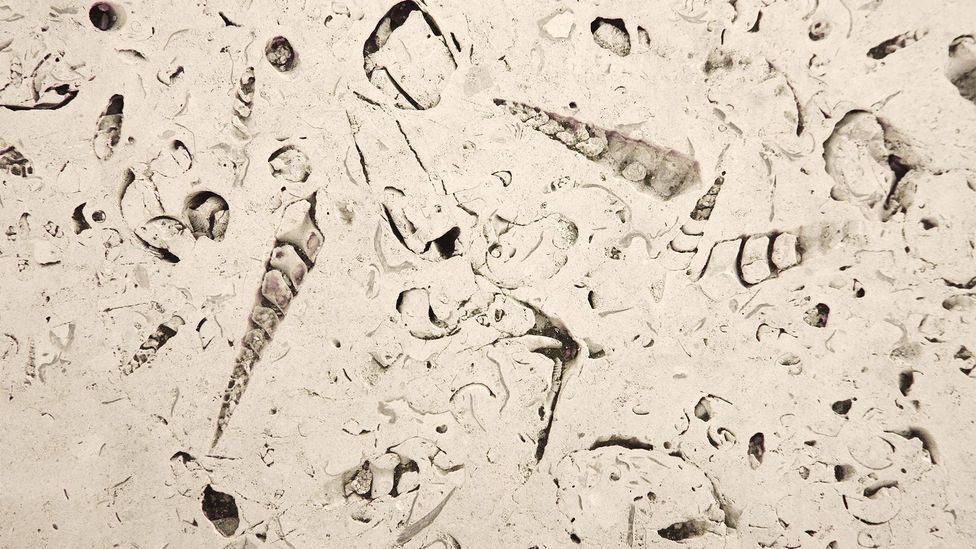

One of the most striking features of Portland Stone is its fossil content. While parts of the Dorset quarries provide architects with completely plain blocks of creamy-white limestone, other layers known as 'roach' are dense with shells, such as brachiopods and bivalves (similar to modern clams or oysters), gastropods (snails) and even the occasional ammonite (spiral-shelled cephalopods).

The Portland 'roach' stone is thick with fossils (Credit: Alamy)

With such abundance, some people assume the Portland fossils are fake, says Siddall. As we're talking over coffee, she subtly gestures at a security guard patrolling the area, who she has spoken with on previous urban geology visits (guards, naturally, are often curious about her behaviour around buildings, she explains). "He's always asking me what I'm doing, and he is absolutely convinced that all the stone used in Paternoster Square is reconstituted. He keeps telling me, 'No, it's not real…somebody's pressed fossils into it.'"

Exactly what it came from, you can't be certain – Ruth Siddall

But the fossils are indeed authentic – around 150 million years old – and today we'll see hundreds. Of all of them, though, Siddall's proudest local find is that grey-brown shape close to St Paul's. It would be easy to miss, since you have to stoop to see it, but its colour and texture suggests it is not a shell. It is bone, she explains, from a vertebrate.

The vertebrate bone in Portland Stone near St Paul's (Credit: Richard Fisher)

One possibility is that it was an ancient turtle or crocodile, Siddall speculates, swimming happily in Jurassic seas before dying and sinking to the seafloor. However, she would like to think it's something even more exciting: part of a pterosaur, which happened to be soaring above the ocean surface before it flapped its last flap, and dropped into the sea.

When identifying fossils or stones with unknown provenance, urban geologists have no microscopes or lab techniques to rely upon

"Exactly what it came from, you can't be certain," she admits. Identifying it would require carving it out of the building, which the owner might agree to if it was a Banksy, but sadly not for a small fossil. However, it's no doubt the most unusual specimen she has found in the area.

When identifying fossils or stones with unknown provenance, urban geologists have no microscopes or lab techniques to rely upon. "Unfortunately you can't take samples…no hammers whatsoever," says Siddall. "A certain part of it is pattern recognition. And I try to keep on good terms with architectural firms."

The black-and-white marble of St Paul's cathedral, which contains carrot-like fossil cephalopods (Credit: Richard Fisher)

Later on our walk, Siddall explains that urban geology is not just about revealing Earth history, but human history too. Most geologists are interested in how a rock came to be, and what it reveals about ancient worlds: how a sedimentary limestone formed in a warm, shallow, tropical sea; how an igneous granite crystallised from blazing-hot magma, or how a metamorphic slate was compressed into layers deep beneath the surface. But urban geology is about the human processes that come afterwards too: how people found a rock, and how it then became a stone. In this second life, a limestone, a granite or slate enters a new stage of its journey through deep time, now shaped by human beings.

Studying urban stone can also capture historical events

And these human choices change through time too, reflecting evolving fashions, politics, performance demands, and architectural preferences. Consider one example: the smooth ornamental granite found in the facades and interiors of many of London's Victorian pubs (of which Siddall has a self-guided walk on her website). She explains that it was chosen to look classy to the average customer, but not too elitist, like the marble of hotels or fine restaurants – and also, pragmatically, to withstand pollution, urine and vomit. The granite was, in short, easy for the Victorian landlord to wipe down after a heavy night of drinking, she says.

Studying urban stone can also capture historical events. In the US, for example, the Washington Monument in the nation's capital has an unintended marble 'unconformity' halfway up, where the stone sharply changes colour. It's not a design feature – it looks like a mistake – so what happened?

The lower portion was built using marble from the town of Texas in Maryland in the mid-1800s, but funding problems and the American Civil War of the 1860s left the monument half-built. When construction continued, that stone was unavailable, so builders had to find a different marble from elsewhere in Maryland. It's like a geological boundary in a rock formation, but here the change represents a war.

The Washington Monument changes colour halfway up, due to funding shortages and the American Civil War (Credit: Alamy)

As we walk in London, Siddall explains that the ground in front of St Paul's steps also tells a hidden historical story. We have just been admiring the limestone and marbles of the cathedral, particularly the "orthocones" in the flooring (a "squid like animal with a hard shell", she explains. "They would have looked like massive swimming carrots.") But for Siddall, the eclectic stones on the plaza nearby are just as interesting. They are a random mix of multiple rock types: some plain and dull, others a deep black, mottled white or iron-red. They don't look particularly well-designed or well-placed – but there's a reason.

Paving stones in front of St Paul's Cathedral show traces of long-dead animals (Credit: Richard Fisher)

Siddall believes they are fragments of the old cathedral and other buildings, before they burned down in 1666. The current St Paul's had a medieval predecessor that was largely destroyed in the Great Fire. The disaster would have left a lot of rubble, she explains, which may have been recycled. "They were using up scraps and bits and pieces," she says. In this way, these stones have had a first life within the Earth, a second life as a cathedral, and now a third as a plaza.

As our walk comes to an end, I realise that I have visited this area of London multiple times over the years, and missed pretty much everything that Siddall has shown me today. In the rush of a city, it's easy to zip past an intriguing fossil or unusual stone, but it's possible to see the urban environment totally differently. You can discover prehistoric worlds, ancient creatures and hidden histories – and it's all in plain sight.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.