If you've ever watched or read Shakespeare's late 16th-Century play The Taming of the Shrew, you'll be familiar with the antiquated gender tropes at play.

The famous story centres on protagonist Petruchio, who exacts various punishments on his headstrong wife Katherine to transform her into an "ideal" pliant and submissive woman.

But modern audiences may be less aware of the diagnosis for Katherine's intolerable wilfulness: an excess of yellow bile (known as "choler") rushing in her blood, leading to a stubborn and hot-headed disposition. Yet more bizarrely, treating the affliction involves Petruchio preventing Katherine from eating "hot" foods that might further inflame her condition. Beef served with mustard, for instance, is strictly off limits.

While baffling to an audience today, humoral theory, which these ideas stemmed from, was a hugely popular framework for understanding health and personality in Shakespeare's time – and for millennia before him.

The desire to classify people and behaviour has been around since recorded history, and probably before – Pamela Rutledge

In addition to irascible "cholerics" like Katherine, there were depressive "melancholics" who suffered a surfeit of black bile; "phlegmatics" (gentle and sedate types who were flooded with phlegm) and "sanguines" (bounding, good-natured extroverts who were suffused with plenty of hot blood, something their ruddy cheeks supposedly attested to).

First originated by scholars in ancient Greece, the theory remained influential up to and including the Enlightenment period. It dictated health and lifestyle advice including which foods people should eat, which medical treatments they should undergo, and even where they should live, all according to their humoral type. The theory faced mounting challenges over the 16th and 17th Centuries, for example with the rise of dissection, greater understanding of the blood circulatory system and the invention of the microscope. Even so, it only faded away gradually.

And while the biological assertions have long been discredited – we aren't all, blessedly, overflowing with bile and phlegm – some of the theory's fingerprints can still be seen on scientifically based psychological models today.

The roots of humoral theory lie in the thinking of Greek pre-Socratic philosopher Empedocles (494-434 BCE), who first proposed that the classic four elements – earth, water, air and fire – were the building blocks of the universe. It is the Greek physician Hippocrates (460-370 BCE), however, who is typically credited with developing the theory of the four humours (yellow bile, black bile, phlegm and blood) and how they impacted the body.

A few centuries later, Greco-Roman philosopher and physician Galen (131-201 AD) codified the theory and described the four temperaments as an expression of the balance of temperature and moisture in the body.

First proposed in ancient Greece and believed in for millennia, humoral theory is now long debunked – but does resemble some modern personality models (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

Galen and Hippocrates' texts birthed a millennia-spanning obsession with temperature and moisture in the body, food and wider environment. These were thought to correspond to the four elements and the four seasons, as well as different stages of life. Melancholics were thought to be cold and dry, and associated with earth, winter and old age. Sanguines, hot and moist, were associated with air, spring and adolescence. Cholerics, hot and dry, were redolent of fire, summer and childhood. And phlegmatics, cold and moist, were related to water, autumn and adulthood.

Appearance was important to identifying someone's humour. "To a very large extent, complexion indicated the humour that dominated in you," says Steve Shapin, an expert in the history of science at Harvard University and author of Eating and Being: A History of Ideas about Our Food and Ourselves. "You find this in Shakespeare. Melancholics were dark of complexion, sallow. Phlegmatics were chubby and moist or greasy-looking, and the choleric people were mean-looking and sharp." (The practice of physiognomy, judging someone's character from their appearance, has been discredited since the late 19th Century.)

Galen's readings became like sacred texts for doctors through the 17th and 18th Centuries – Steve Shapin

But the humours were not immutable. It was thought internal balance could be achieved partly through consuming food that complemented one's inner composition. Phlegmatics, for example, were advised not to eat peaches and melons, says Shapin. "They were too watery." You might even be directed to live in warmer, colder, drier or wetter terrain to ensure harmony between your internal and external environments.

These ideas were remarkably durable. "Galen's readings became like sacred texts for doctors through the 17th and 18th Centuries," says Shapin. "Discovering what people were like, and the language that allowed doctors to advise people on how to live, was a really stable feature of culture."

Eventually, the theory's influence diminished, to be replaced by emerging nutrition science in the mid-to-late 19th Century.

Despite the now-discredited knowledge underpinning it, Shakespeare's portrayal of personality archetypes are still familiar to modern audiences. "When I teach Romeo and Juliet, my students are like, 'Oh my God, Romeo is such an emo'," says Sarah Dustagheer, a literary historian at the University of Kent, who studies playwriting and performance in London in the Early Modern period.

"The 17th Century was very different from our society, but there are some fundamentals of human emotion and human experience that haven't changed," she adds. "What's changed is the way we interpret them."

This is something influential German-British personality theorist Hans Eysenck discovered when he used an approach called "factor analysis" in the 1950s. It involved studying personality variables (such as aggression or shyness) to see how they related to one another, and whether they could be explained by broader, underlying dimensions.

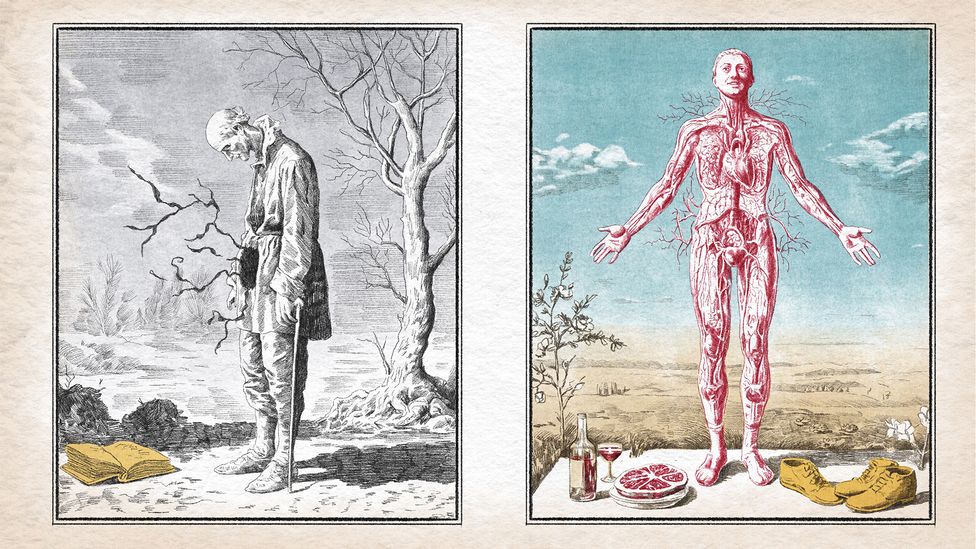

Humoral theory's melancholics were depressive and suffered a surfeit of black bile, while sanguines were good-natured extroverts suffused with hot blood (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

Eysenck's first models set out two main personality dimensions which he labelled "neuroticism" and "extroversion". (The term extroversion had previously been coined by famous psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung, but with a slightly different meaning.)

Eysenck viewed extroversion as a function of how sensitive someone was to external stimuli. Extroverts, he said, were less sensitive, meaning they found a higher level of stimulation exciting – think big parties, loud music, bright colours and so on. Introverts were the opposite. Neuroticism, meanwhile, was a function of how intensely people responded to stress and their susceptibility to negative emotions.

Pamela Rutledge, director of the Media Psychology Research Center in Nevada in the US, says Eysenck saw personality as reflecting the make-up of people's nervous systems. "He argued that individuals inherit a type of nervous system that affects their ability to learn and adapt to the environment."

He found that combining his two dimensions in different ways created four "types" that sounded eerily similar to the four humours of the ancient taxonomy:

• High neuroticism and high extroversion = choleric

• High neuroticism and low extroversion = melancholic

• Low neuroticism and high extroversion = sanguine

• Low neuroticism and low extroversion = phlegmatic

Eysenck took this as evidence of the validity of his approach. It seemed to "match people's observations and intuitions about personality that had been around for thousands of years", says Colin DeYoung, a professor of psychology at the University of Minnesota, US.

Eysenck was also struck by the ingenuity of ancient scholars in connecting personality with underlying biology. While he wasn't under the illusion that substances like black bile contributed to the differences between people, he developed new theories about the neurobiological basis of our personalities. This is a thriving area of research today, says DeYoung, which has, for example, linked extroversion with the dopamine reward system in the brain.

In reality, most people are somewhere near the average on personality scores: something a categorical system can't really handle – Colin DeYoung

Today, Eysenck is a controversial figure due to his racist beliefs about IQ, which have long since been debunked. While his models have now been superseded, the current dominant model of personality, the Big Five personality model, still includes his two major dimensions, neuroticism and extraversion. Developed by a number of research groups in the 1990s, this model further adds openness, conscientiousness and agreeableness. It posits that the basic structure for personality is composed of differing intensities of these five factors. A number of studies claim these five dimensions are statistically independent of one another.

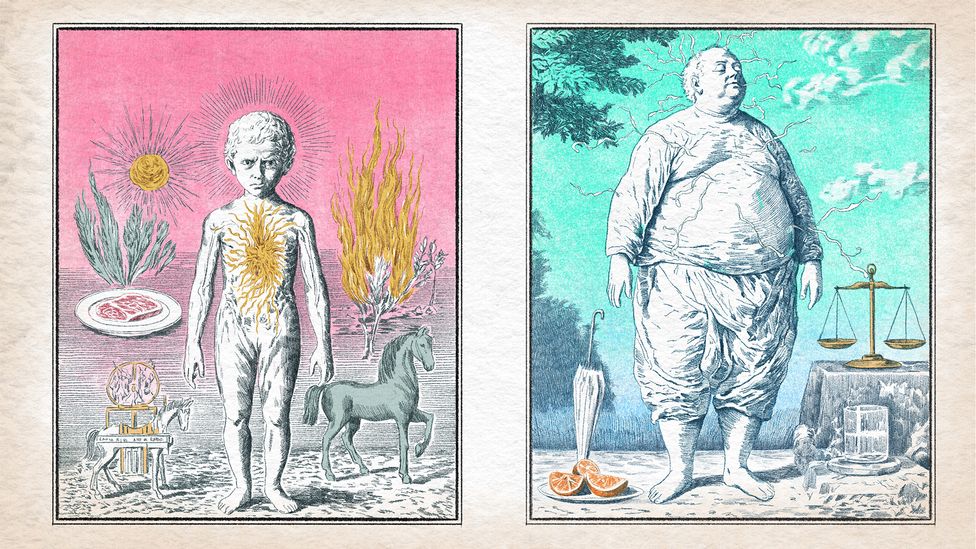

Cholerics were supposedly wilful and stubborn due to an excess of yellow bile, while phlegmatics were gentle, sedate and flooded with phlegm (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

But other researchers have found that certain dimensions tend to correlate. "Not only [that], but those correlations had a pretty regular and reliable pattern," says DeYoung.

Analyses by DeYoung and others have found that extraversion and openness typically cluster together, as do low neuroticism, agreeableness and conscientiousness. "So you could take those correlations and make two higher order factors above the Big Five," says DeYoung.

DeYoung and his colleagues conceptualised these two clusters as "plasticity" and "stability" respectively. Combining these two factors, he adds, yielded a familiar-sounding four-type personality model:

• High plasticity and low stability = choleric

• High plasticity and high stability = sanguine

• Low plasticity and low stability = melancholic

• Low plasticity and high stability = phlegmatic

"Once again, this was sort of parallel to the old humours," says DeYoung, with a chuckle.

However, there is disagreement on whether these two higher order factors really exist. "Personality psychologists have argued for a long time over the balance between parsimony and nuance," says Rutledge. Simplifying personality down to two factors is appealing "as it provides an effective shorthand for making sense of human behaviour", she says. But some scientists argue that they are merely a byproduct of overlap between some of the personality traits assessed by most Big Five questionnaires, but that other personality traits are indeed a pure expression of just one of the Big Five.

There is also a worry from the clinical side "that collapsing traits into meta-traits risks oversimplifying the diversity of individual experience that may be central for tailoring interventions", Rutledge adds.

More like this:

• The places where the voices in your head are seen as a good thing

• How noise sensitivity disrupts the mind, brain and body

• Why you are not as selfish as you think

In the age of online personality quizzes and Myers Briggs letter-strings (not to mention star signs) in dating bios, many researchers are quick to caution that our fixation with "types" is not scientific. But does DeYoung's work hint that our personalities are a little easier to boil down after all?

"The answer is not exactly," says DeYoung. Personality psychology has reached a consensus that types can sometimes be a useful way to summarise someone's standing on different dimensions, he says. The issue is there aren't "clear, categorical entities in nature", he says.

Labelling people with types à la Myers Briggs, a debunked personality test developed in the 1940s by mother and daughter Katharine Cook Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myers, faces the issue of arbitrary cut-offs between categories. In reality, DeYoung says, scores fall along a bell curve and most people are somewhere near the average – something a categorical system can't really handle.

Nevertheless, as Shakespeare was once riveted by cholerics and sanguines, today many of us remain entranced by Type As, ENTJs and Scorpios. "Classification is our built-in mechanism for organising information so we can understand, learn and interact with the world," says Rutledge. "The desire to classify people and behaviour has been around since recorded history, and probably before."

--

For trusted insights into better health and wellbeing rooted in science, sign up to the Health Fix newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.