Public data can be as revealing as private data

Charles Miller

edits this blog. Twitter: @chblm

A review of Dataclysm by Christian Rudder.

The oceans of information sloshing around the internet offer insights that have never before been available. While mass data is nothing new – censuses have been around since Roman times – internet data is so vast and varied that an element of creativity can be applied to its analysis with intriguing results.

It’s a game that anyone can play. Google trends compiled data from enquiries about the Conservative leadership election. Take a look at the top five questions asked about each of the candidates. First for each was “Who is [name]?” except about Theresa May, where “who is” comes second to “How old is Theresa May?” (Answer: 59). For what it’s worth then, Google’s data supports the intuition that May was already better known than her rivals. But this is thin gruel compared to the kind of data orchestrated by Christian Rudder in his book Dataclysm.

Like any other kind of journalism, data journalism is best when drawing on exclusive sources. Rudder found himself sitting on a mountain of fascinating stuff as the co-founder of a dating website called OkCupid. His book isn’t a collection of confessional tales stolen from hapless singles; rather it’s what Rudder has gleaned from his users as a group thanks to his formidable skills as a Harvard maths graduate. With ten million people using OkCupid each year, there’s plenty to work with.

You're the one for me

Rudder makes the most of the interplay of age, place, self-description, messaging behaviour and sexual preference. Nothing he reports is indiscreet and yet it’s deeply intimate, revealing things his customers don’t even know about themselves.

Take a very basic measure: OkCupid asks its users to rate photos of each other on a five star scale of attractiveness. When men rate women, you get a standard bell curve centred on the mid point of the attractiveness scale. In other words, men find most women to be of average attractiveness, with falling numbers towards the extremes of ‘very attractive’ or ‘very unattractive’. So what? Well, Rudder suggests it’s nothing less than a “small miracle” that despite their bombardment with images of “the supermodels, the porn, the cover girls, the Lara Croft-style fembots”, men’s visual expectations of real women are so realistic.

It doesn’t have to be that way. If you look at women’s view of men, the most common rating women give is barely a quarter of the way up the attractiveness scale. In other words, women seem to be judging potential partners against a more attractive population of men that those in the real world. (And Rudder has stats to show that his customers are representative of the population as a whole, so it’s not that men who using dating sites are less attractive.)

As to how you’d interpret this gender difference, there are many possible theories. The point is that with so much data, it’s a robust finding and not just some flaky survey.

Rudder shows that data can illuminate trends that stretch back way before the internet was invented, to answer questions like this: is the internet making us less literate?

No it's not, Rudder concludes, like this: he starts with the Oxford English Corpus (OEC), a collection of contemporary writing in English from all sources. He makes a list of the top 100 words (which, amazingly, account for about half the words in all writing). Now he scrapes Twitter for its most common 100 words.

What you find is that the top 100 Twitter words are on average longer (4.3 characters) than the OEC top 100 (3.4 characters). An academic has independently found that the average word length in Hamlet is less than that written by P.G.Wodehouse (1881-1975), and that both are less than the average on Twitter. Far from reducing us to a vocabulary of “lol”s and IMHOs, then, you could argue that the internet is making us more, well, palaverous or circumlocutory.

For something more profound, try this: are we living more in the present and becoming less aware of history?

Rudder investigates, starting with Google Books’ searchable collection of 30 million texts, which go back to publications from 1800. He searches for year names, every fifty years, starting in 1800. He finds that mentions of “1850”, for instance, peak in 1851, at a rate of 35 in each million words written. When you do the same for “1800”, “1900”, “1950” and “2000” there’s a clear trend. As time goes on, each year features more prominently in the writing of its time, with “2000” appearing almost 250 times per million words. So, yes, as Rudder concludes, “with each passing year, we’re getting more wrapped up in the present.”

But it’s the results from his own dating site that produce Rudder’s most original findings. The book is full of graphs and lists, so you need to be ready to pay attention in order to understand what he means, for instance, by his lists of the most characteristic self-descriptions broken down by gender and ethnicity. Then there’s the interesting section that maps the frequency of people identifying as gay against the acceptance of gay marriage in different US states. He uses the results to extrapolate what level of self-declaration you’d expect in a world free of social pressure.

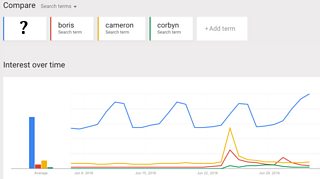

As I said, you don’t need privileged access to generate your own data findings. Back to Google Trends: I put in the words “Boris”, “Cameron” and “Corbyn” to see which had been most searched for in the past few weeks. It turns out that Cameron comes out top, only overtaken by Boris when he stood down:

But what’s that blue line at the top, so much more popular than the others and peaking every Saturday night? Well, it’s a line that proves the British public keep their political crises in perspective: it’s “pizza”.