How a graphic novel style can tell the most powerful of human stories

Marc Ellison

Freelance photojournalist and BBC Scotland data journalist @marceellison

The graphic novel is traditionally the realm of the muscle-bound superhero fighting evil-doers, bedecked with cape and sporting underpants on top of iridescent tights.

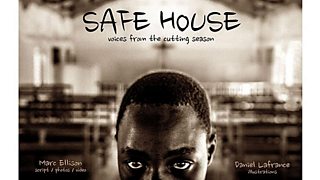

And yet it is three very real Tanzanian girls who grace the pages of my latest comic book project Safe House.

While the protagonists may be atypical for the format, these girls exemplify what any graphic novel aims to chronicle: a battle between good and evil, and characters who overcome the odds to inspire us.

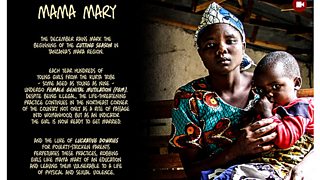

The December rains mark not only the end of the school term but the start of the four-week period when girls in Tanzania’s northern Mara region typically are forced to endure female genital mutilation (FGM).

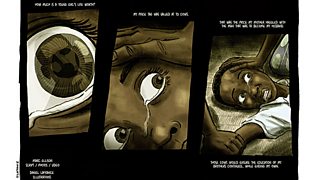

Daniel Lafrance's illustrations depict the horror of a young girl's ordeal

The pernicious practice has been illegal in Tanzania since 1998, but here the Kurya and Mungurimi tribes still believe the life-threatening procedure is a mandatory rite of passage into womanhood – and an indicator to men in the village that the girl is now ready to get married.

A 2010 government survey found that in the Mara region 40% of girls and women had been cut.

The graphic novel documents – through illustration, photography and video – the stories of two such girls as they flee to the eponymous safe house to escape being cut by their parents. But the comic begins with the story of a third woman who wasn’t so lucky.

If ever there was a poster child for why a safe house was needed in Mara, or what impact it has made in the two short seasons since it was constructed, it’s Mama Mary. Forced to undergo FGM aged just 11, she was married to an abusive older husband at 13. Starting from their wedding night, Mama Mary was subjected to a decade of sickening physical and sexual violence – all for the price of 10 cows.

Here, she talks about her life:

The girls’ stories are told via an interactive, animated and multimedia format I first experimented with last year to tell the post-abduction stories of female, former child soldiers in Uganda through Graphic Memories.

Long-inspired by the work of Joe Sacco and Art Spiegelman, I wanted to push the digital boundaries by producing a 2.0 version of a graphic novel for an increasingly tech-savvy, multimedia-demanding, tablet audience.

One of Christian Mafigiri's illustrations from Graphic Memories

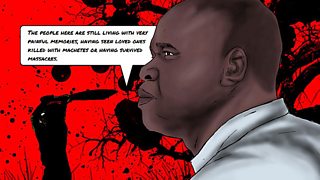

Created with illustrations from Christian Mafigiri, Graphic Memories advanced beyond static imagery and text – beyond a one-way, linear narrative – and allowed the reader to engage in a virtual ‘conversation’ with four women struggling to reintegrate into their communities.

Scrolling down the page triggers the animation of each woman's story. But you can also choose to pause the narrative, and hear detailed personal testimony from the women or other characters like trauma counsellors and NGO workers. (Christine, pictured below, tells how she is haunted by nightmares from her past in this video account.)

Produced for Al Jazeera and the Toronto Star, and supported by a grant from the European Journalism Centre, it took third prize for multimedia innovation at the recent World Press Photo Awards, beaten only by two projects from the mighty New York Times.

It encouraged me to utilise the format to document another African story, the prevalence of child marriage in Tanzania.

The illustrated approach has many advantages over traditional storytelling formats. Not only does a comic book style allow a journalist to plug the narrative gaps and capture events we couldn’t witness first hand, but more importantly – as with the case of the 12-year-old Dorika (below) – it allows reporters to maintain a vulnerable source’s anonymity.

Despite these advantages, care must be taken to not abuse the medium by exaggerating, sensationalising or fictionalising events. With Safe House, Canadian artist Daniel Lafrance and I were conscious of removing the ‘graphic’ from the graphic novel, doing our best to minimise displays of abuse and sexual violence, while hopefully, conveying the pain and horror suffered by victims.

And by relying on numerous detailed interviews with each girl, as well as reference photographs from the field for Lafrance, we were able to portray as realistic a representation as possible of life and events in order to transport the reader to the Mara foothills.

In different contexts, the graphic novel approach can also be harnessed to educate secondary school and university-level students about issues in the developing world. I’ve been contacted by a Canadian NGO which will be using the downloadable Swahili version of Safe House to educate Maasai schoolgirls about the effects of FGM and child marriage – and more importantly, that they can say ‘no’.

Despite the undeniable impact of graphic journalism, it’s still very much a maturing format. While outlets like the BBC and The Guardian have tried it out to tell non-fiction stories, many editors can be put off by the time and resources these projects can suck up.

I've been very fortunate, not only to have had funding bodies believe in me, but lucky that BBC Scotland has allowed me to take unpaid leave from my job as a data journalist to pursue these passion projects.

And that's what they're all about: passion. Graphic Memories took three years of knock-backs from grant bodies and outlets before it was finally funded and produced. (A separate animated long-form piece was commissioned by German news website Zeit Online.) The two graphic novels each took between three to five months to complete, taking up all of my evenings and weekends.

But like anything that’s slow-cooked, the end result is worth it.

I believe the positive reaction to my collaborations, and indeed to work like Dan Archer’s experimentation with Virtual Reality, shows that audiences are becoming more accustomed and responsive to innovative forms of digital storytelling.

While there may be an absence of cape-wearing superheroes in my comics, they are instead full of stories of girls and women who are very much heroes in their own right, and whose stories need to be heard.

All photography by Marc Ellison, all Safe House illustrations by Daniel Lafrance.

Published solely by the Toronto Star, Safe House was produced with aid from the Fellowship for International Development Reporting. Marc Ellison has worked extensively across Africa since 2011. He discussed his graphic novels work at London’s recent Polis conference 2016: Journalism and Crisis.

Blog: A stripped down telling of some of the world’s toughest stories

Our sections on: